What We Do

Collection and Preparation

Beginning in the 1950s, the project's original staff began collecting copies of documents from repositories across the United States as well as around the world. In the days before the advent of the internet and digital scanning (and before the widespread availability of computers and even modern photocopiers), obtaining images often posed numerous challenges, not the least of which involved identifying where material might be housed and traveling to those sites and combing through their collections. Though the document-acquisition effort was largely completed by the 1980s, new material occasionally still comes to light and is incorporated into our volumes and supplements.

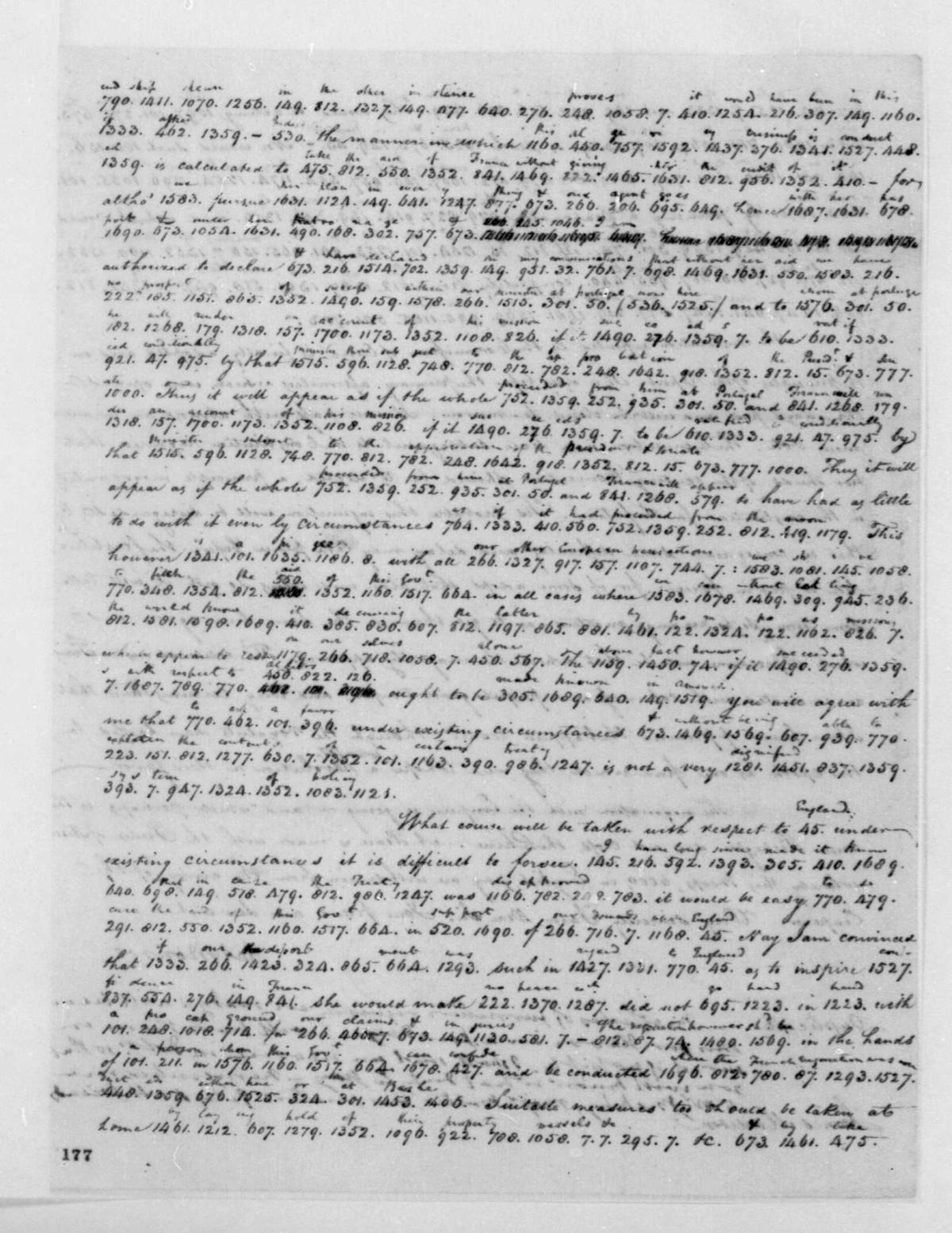

Once the documents were acquired and cataloged, project staff began reading and transcribing the manuscripts. These tasks brought their own hurdles, which included the difficulties posed by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century handwriting, manuscripts in poor condition, and the limitations of the copying technology. Some of these challenges are evident in these pages written to Madison by Tench Coxe, ca. 22 November 1801.

|

|

By the 2010s, transcription of all documents was complete. But the rest of our work continues. Each document is proofread first by the volume editor, who compares the transcribed text with the original. All documents then receive a tandem proofreading—that is, one staff member reads the text aloud, word for word and punctuation mark for punctuation mark, to another staff member, who confirms the accuracy of the transcription. When feasible, any remaining ambiguities are checked against the original documents themselves.

During this process, we decide how each document will appear in the volume. The vast majority of documents are printed in their entirety. Other documents that are routine, repetitive, extremely lengthy, or difficult to reproduce in their original format may be abstracted. For abstracts, editors usually quote the entire body of the document but omit salutations and complimentary closes. Documents occasionally refer to other materials that we are unable to locate; in such cases we include a "letter not found" entry describing what we know about the missing document.

Research and Annotation

We then turn to annotating the documents. We try to determine the dates of undated letters, identify correspondents in unsigned and unaddressed letters, and describe persons and subjects with which our readers might be unfamiliar. This step is especially important in the Secretary of State and Presidential Series, where correspondents often refer to European, South American, and Mediterranean affairs; to seizures of American ships abroad; and to little-known and/or foreign individuals and events.

Final Checking

More proofreading! Our editors reread all of the letters as well as the annotation, again verifying the accuracy not only of the transcriptions but also of the annotation. Our copyeditor then reviews the entire manuscript for style, consistency, and any other issues that might crop up. And finally, after one more review by the editor in chief, we submit the manuscript to the University of Virginia Press.

Volume Production

The press sends the manuscript to the compositor, who typesets the volume and sends us page proofs to review. We then conduct another tandem (out-loud) proofreading of the entire volume, comparing the pages against the manuscript. At this stage, we also prepare, check, and proofread the index. After we submit the corrections and index to the press, we receive revised pages. The index is then proofread and any necessary further corrections are made, and when the manuscript is finalized, it is sent to the printer, which creates the bound volumes.

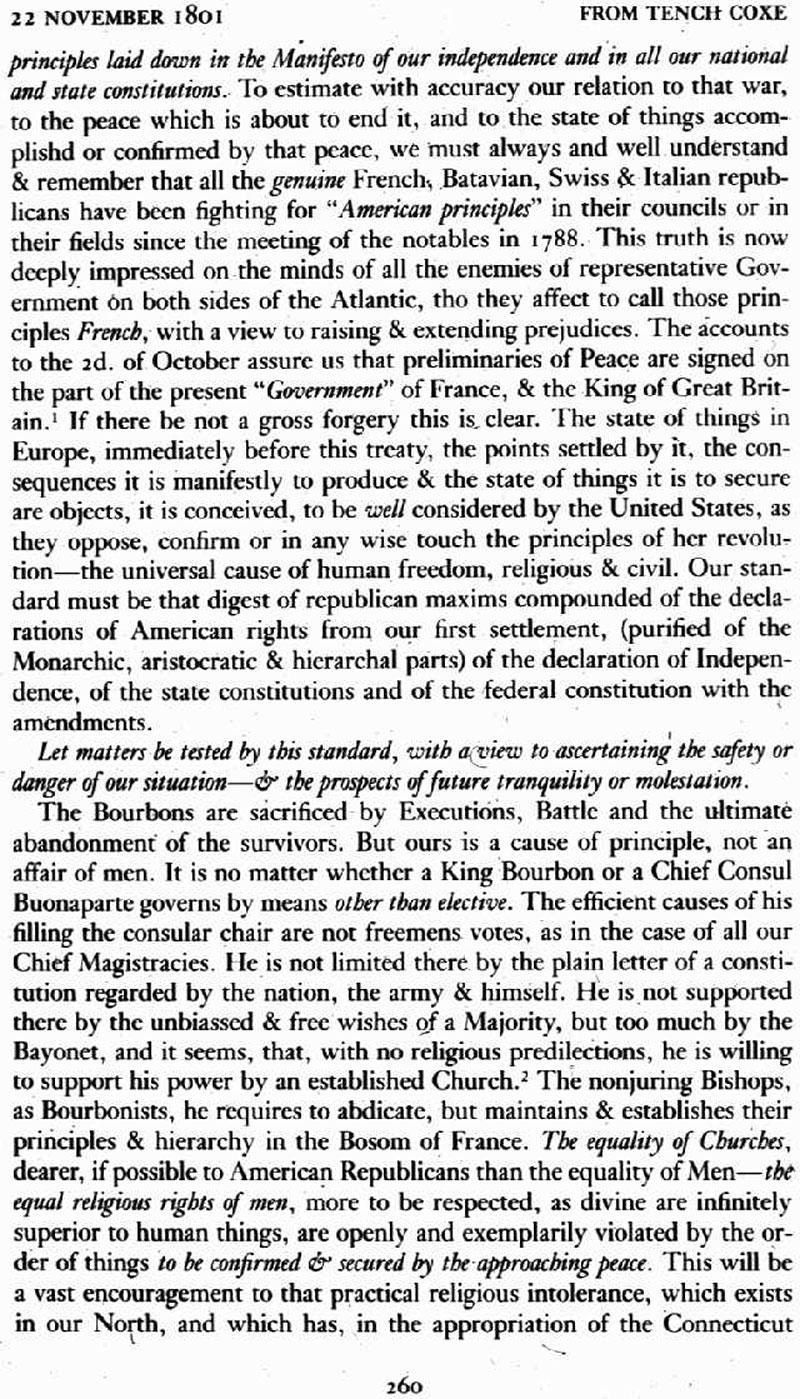

About a year after we submit the manuscript to the press, we receive the finished book. These images show the published version of the Tench Coxe letter above.

|  |

While one volume is in production, our editors are already working on subsequent volumes, enabling us to release about one volume per year.

Code

James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and others used codes for a variety of reasons. Mail was more insecure in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries than it is today. Particularly in the late 1790s, private correspondence that went through the U.S. mail was subject to inspection by postmasters, many of whom were Federalists, and they at times tampered with letters and/or published their contents in newspapers. To avoid this fate, Madison and Jefferson often sent their letters unsigned or partially in code.

Encoding was also used for both personal and official correspondence that traveled via the ocean. Particularly during the Napoleonic era, when British and French ships frequently seized vessels accused of violating blockades, diplomatic officials often not only encoded sensitive correspondence but also sent multiple copies by different routes.

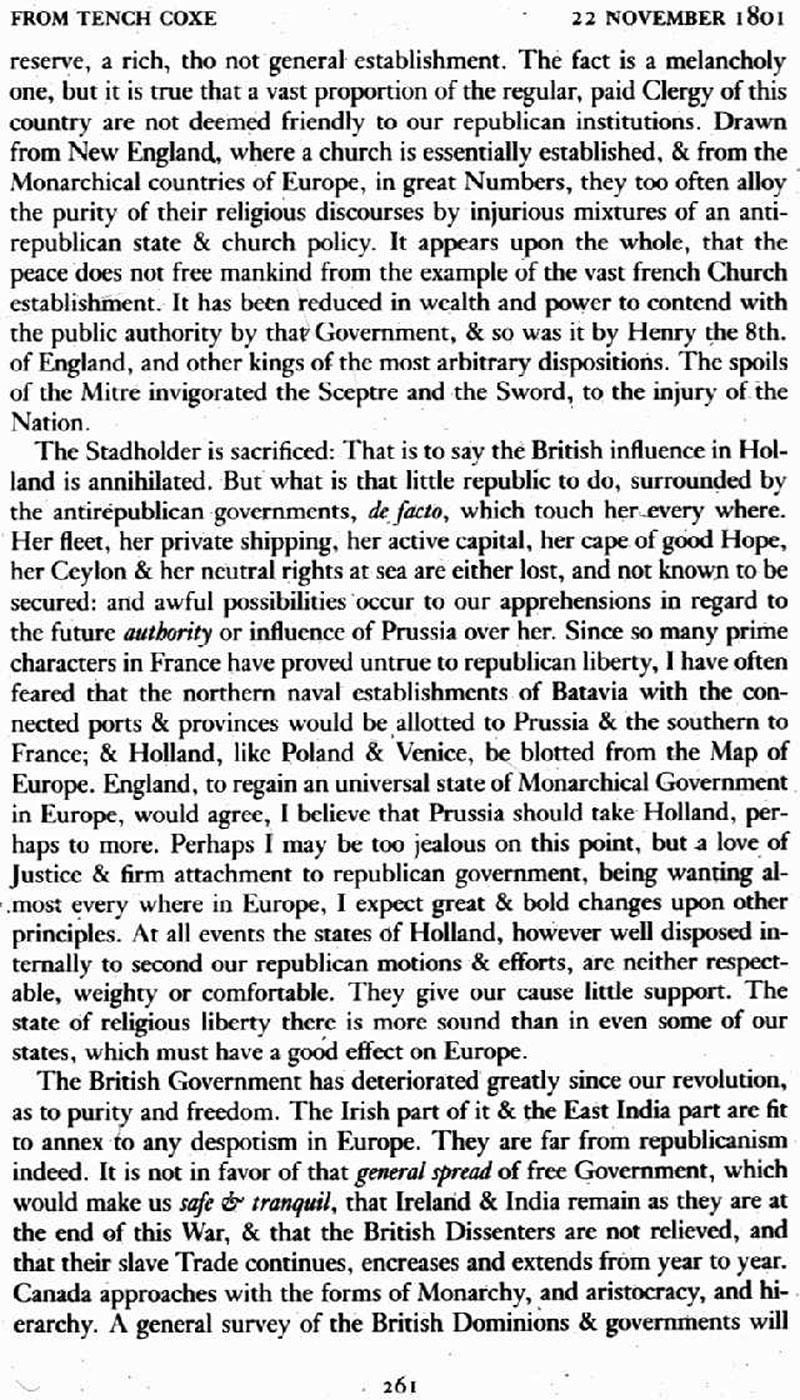

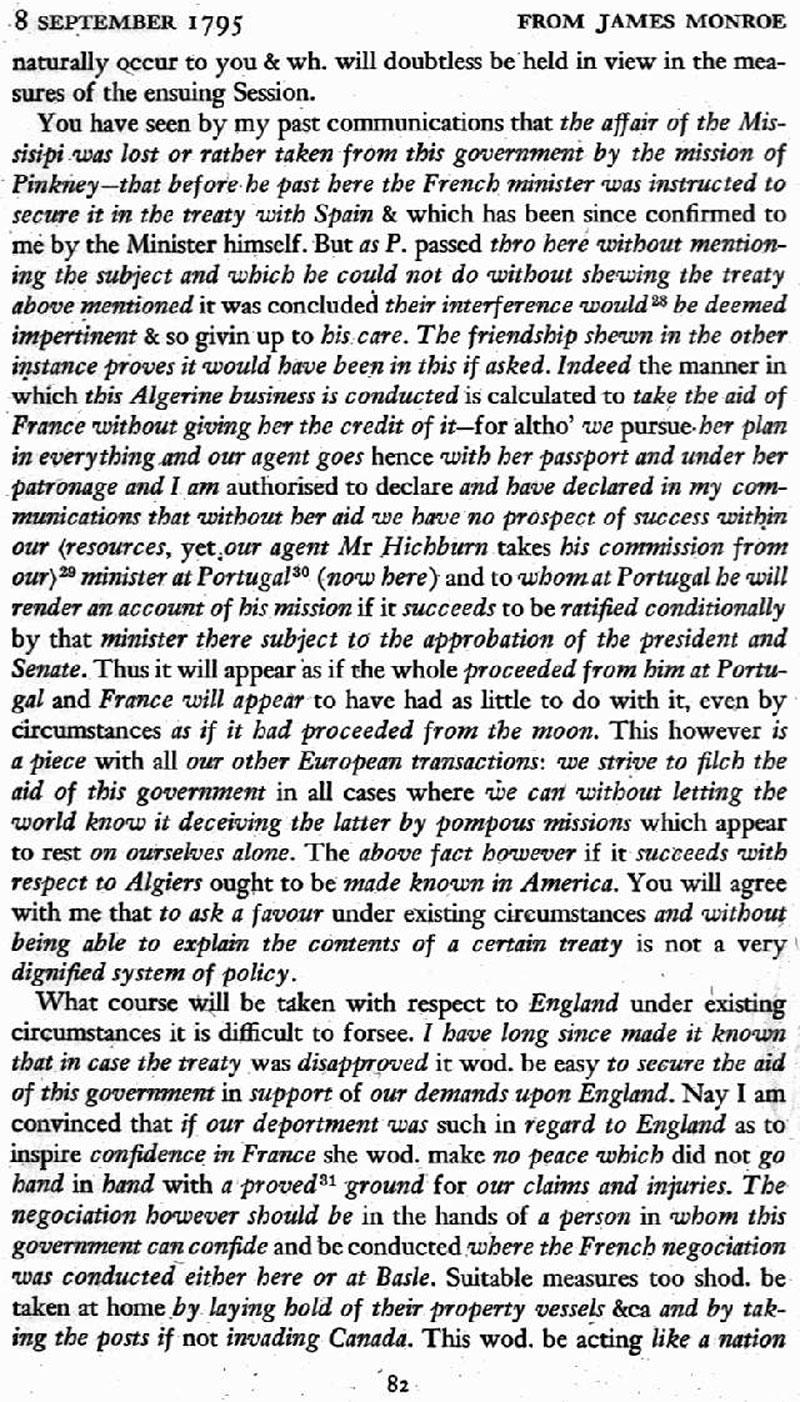

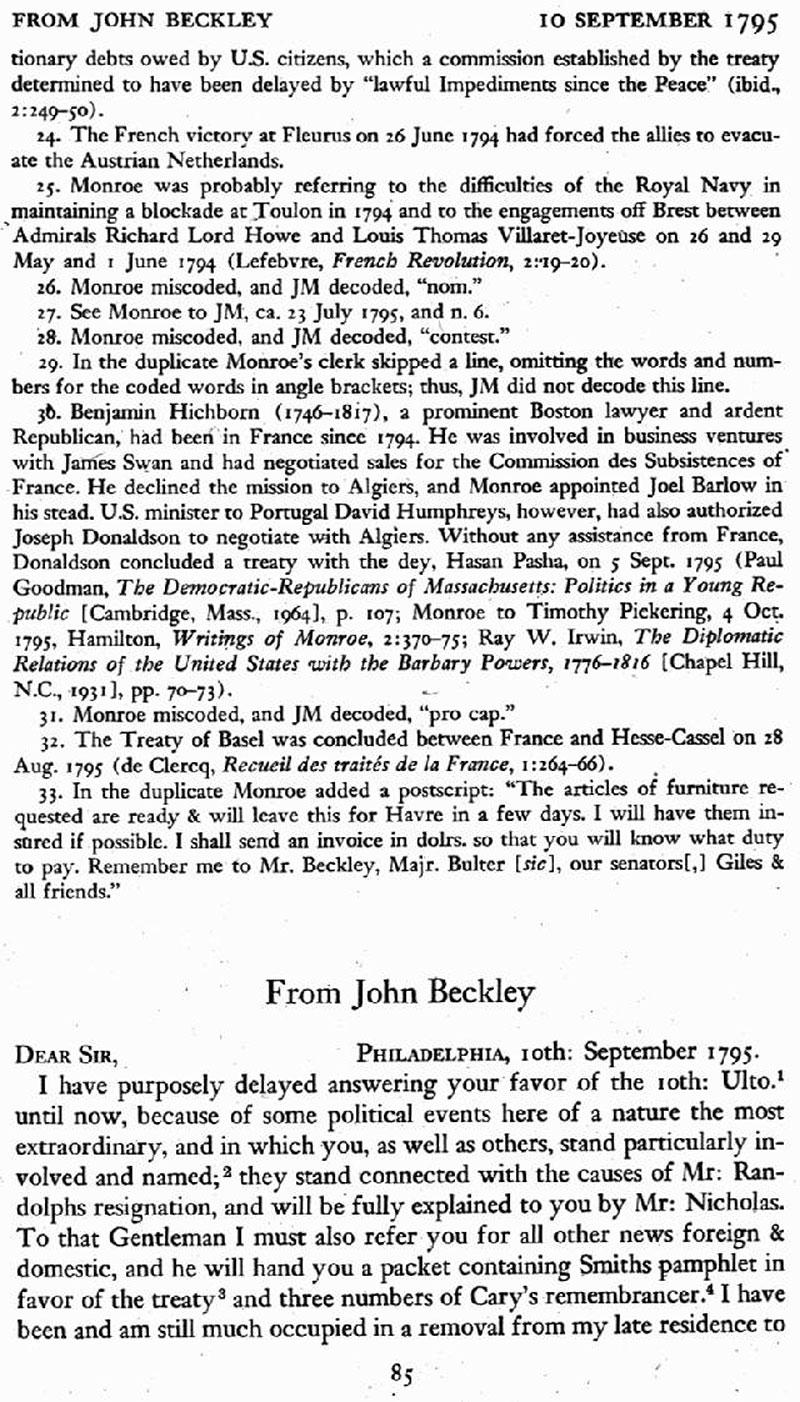

James Monroe sent the coded letter below to Madison on 8 September 1795, when Monroe was U.S. minister to France. The code for this letter was used by Madison, Monroe, and Jefferson and is a simple number code: letters, words, or combinations of letters are represented by numbers. When the letter reached Washington, D.C., Madison or his clerk used the key to decode the encoded words and then wrote them in above the coding.

|

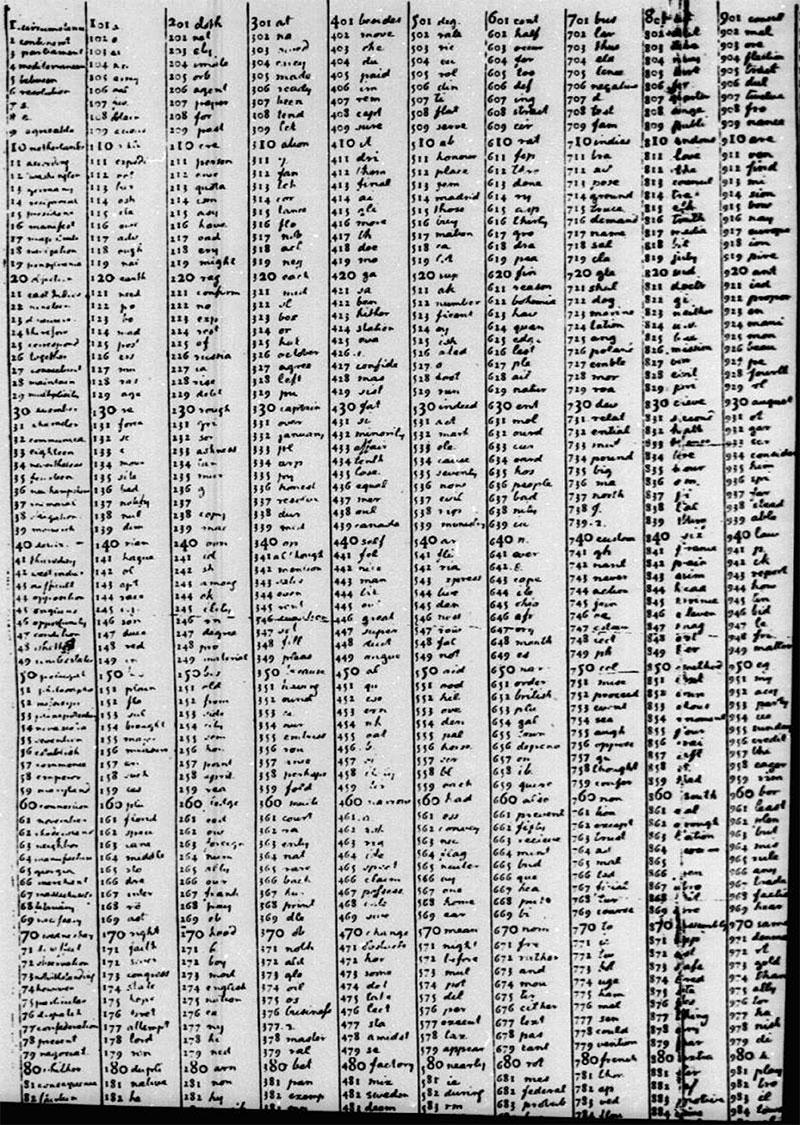

In this case, the code key has also survived.

|

When we print the letters, we present the decoded text in italics to distinguish it from the words that were not encoded in the original.

|

Not surprisingly, errors in encoding and decoding were common. Whenever possible, therefore, we decode letters again ourselves using the key and print that version, noting any discrepancies between our version and the original decoding. We thus have a record not only of what the letter's author intended to say but also of what message the recipient received.

|

In some cases, such as the code used by Charles Pinckney when he was U.S. minister to Spain in the early 1800s, keys have not survived. In those instances, we print the original decoding and/or use it to reconstruct the key as much as possible.

A Coding Mystery!

We have one document that we have not been able to decode—a 20 February 1808 letter to Madison from John Armstrong, U.S. ambassador to France. Armstrong had replaced his brother-in-law, Robert R. Livingston, in that post in the fall of 1804, a year and a half after Livingston and James Monroe negotiated the Louisiana Purchase. Livingston and Monroe believed that the purchase included the territory then known as West Florida, which extended from Baton Rouge in the west to the Perdido River (now the boundary between Alabama and Florida) in the east, an assessment with which Madison and President Jefferson agreed. But the Spanish government refused to hand over West Florida to the United States. Armstrong discussed the situation with the French government and reported to Madison in 1805 that Napoleon had offered to mediate negotiations between the United States and Spain. In essence, Napoleon would force Spain to sell and then claim the proceeds in the form of debt payments that Spain owed to France. The Jefferson administration agreed to try this approach, convinced Congress to sign on, and sent James Bowdoin to negotiate in Madrid. But the Spanish government delayed and Napoleon reneged on his part of the deal despite Armstrong’s nagging. Armstrong also protested Napoleon’s 1806 Berlin Decree and 1807 Milan Decree, both of which threatened American shipping with capture and confiscation as part of France’s economic warfare against Britain. Armstrong demanded to know whether the decrees would be enforced against U.S. ships, but the French government refused to give clear answers while using the possible effects of the decrees to motivate American compliance with additional schemes exploiting the U.S. interest in Florida. On 15 February 1808 Armstrong reported to Madison that Napoleon had offered to turn a blind eye to an invasion of Florida if the United States would enter a military alliance with France against Britain. On 22 February 1808 Armstrong wrote again to convey his belief that Napoleon intended to enforce the decrees against U.S. ships. The mystery letter was written between the 15 and 22 February letters, and we can only surmise that it concerned some of the same problems discussed in the letters that preceded and followed it.

The letter is written in an unknown code and contains shorthand as well. The 15 and 22 February letters are partly written in the 1,600-element numerical code that Armstrong used for all his other encoded correspondence, but the key to that code, which we’ve partially reconstructed, doesn’t work for the 20 February letter. Nor do any of the other State Department code keys that we’ve acquired or reconstructed or any of the keys published in Ralph Weber’s United States Diplomatic Codes and Ciphers, 1775–1938 (Chicago, 1979). None of the text of the 20 February letter is decoded on the letter itself, and we have no evidence that it ever was decoded or that Madison acknowledged receiving it.

If you have any success in decoding it, please email us at jmadison@virginia.edu